- Network Effects

- Posts

- The Convergence of Software & Service

The Convergence of Software & Service

The Full-Stack AI Manifesto

Software might have eaten the world in the last decade, but it left plenty of legacy services industries on the plate. The most valuable companies of the next decade won't just sell software to dinosaurs; they'll make them extinct.

This essay explores the emergence of full-stack companies that are blurring the line between software and services. While promising, this model demands rigorous execution to avoid common pitfalls.

(Thanks to Evan Lyseng for reading draft and suggestions)

“You could build an AI agent and sell it to law firms. That's what most people do. Or, you could start your own law firm, staff it with AI agents, and compete with the existing law firms. That, my friends, is going full-stack. You could do this for any industry, especially one dominated by slow-moving incumbents. Instead of selling to the dinosaurs, you could make them extinct.”

Established Beliefs on the Software and Service Divide

For decades, the software and service industries largely operated on distinct, parallel tracks. Software scaled through code as a form of leverage, achieving exponential growth with minimal marginal cost. Services scaled linearly, tied directly to human effort and capacity.

Specialization arises because the internal costs of coordinating every disparate activity within a single firm exceed the costs of conducting those activities externally through specialized market players.

As a result, we see firms focus on core competencies to achieve efficiency, lower costs, and deeper expertise in their niche, forming a network of specialized entities that collectively reduce the overall transaction costs for the economy. For example, in the semiconductor industry, design (e.g., Nvidia and AMD) is separated from fabrication (e.g., TSMC).

Convergence of Service and Software

As the software industry matures with an array of greenfield solutions (i.e., software for “X” industry), it often hits a ceiling because it doesn't fundamentally alter the underlying computational constraints of the service itself. It provides tools but largely leaves the service's core human-dependent cost structure intact.

However, the tide has turned.

The prevailing belief that these are fundamentally separate business models is becoming obsolete. The next generation of software, powered by AI, isn't just a tool; it's an embedded agent of change within workflows. It augments decisions, automates significant subsets of tasks, and eats into labour budgets.

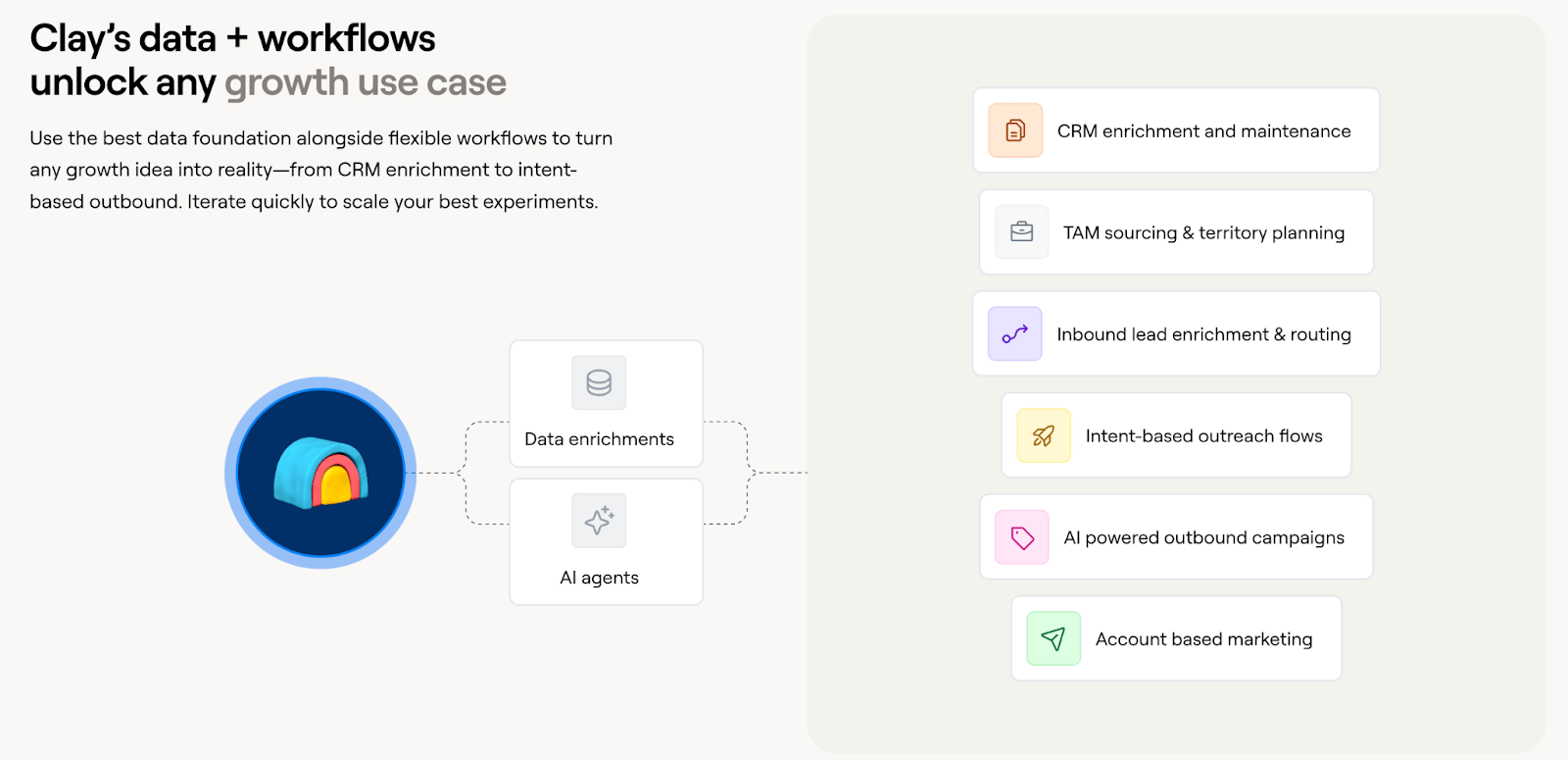

Take CRM as an example. Traditionally, it organized customer data. Tomorrow's AI-native CRM won't just store information; it will recommend follow-up actions, draft personalized emails, integrate call transcripts into notes, and even proactively identify at-risk accounts for human intervention. This blurring of lines forces a critical question:

When software can perform, augment, and even automate core service functions, why keep the two distinct?

The benefits of AI in this context can be distilled into three levers for value creation:

Augmentation: Perform existing workflows cheaper, faster, and better.

CRM example: lead classifications, content campaign generationIntelligence: Analyze vast amounts of data to uncover insights and patterns that are too costly or time-consuming for humans to find

CRM example: analyze lead warmth based on transcripts & social media dataOpportunity Expansion: Perform tasks that were previously impossible for humans, creating new capabilities and possibilities

CRM example: Scale outreach flows, AI-enabled A/B testing

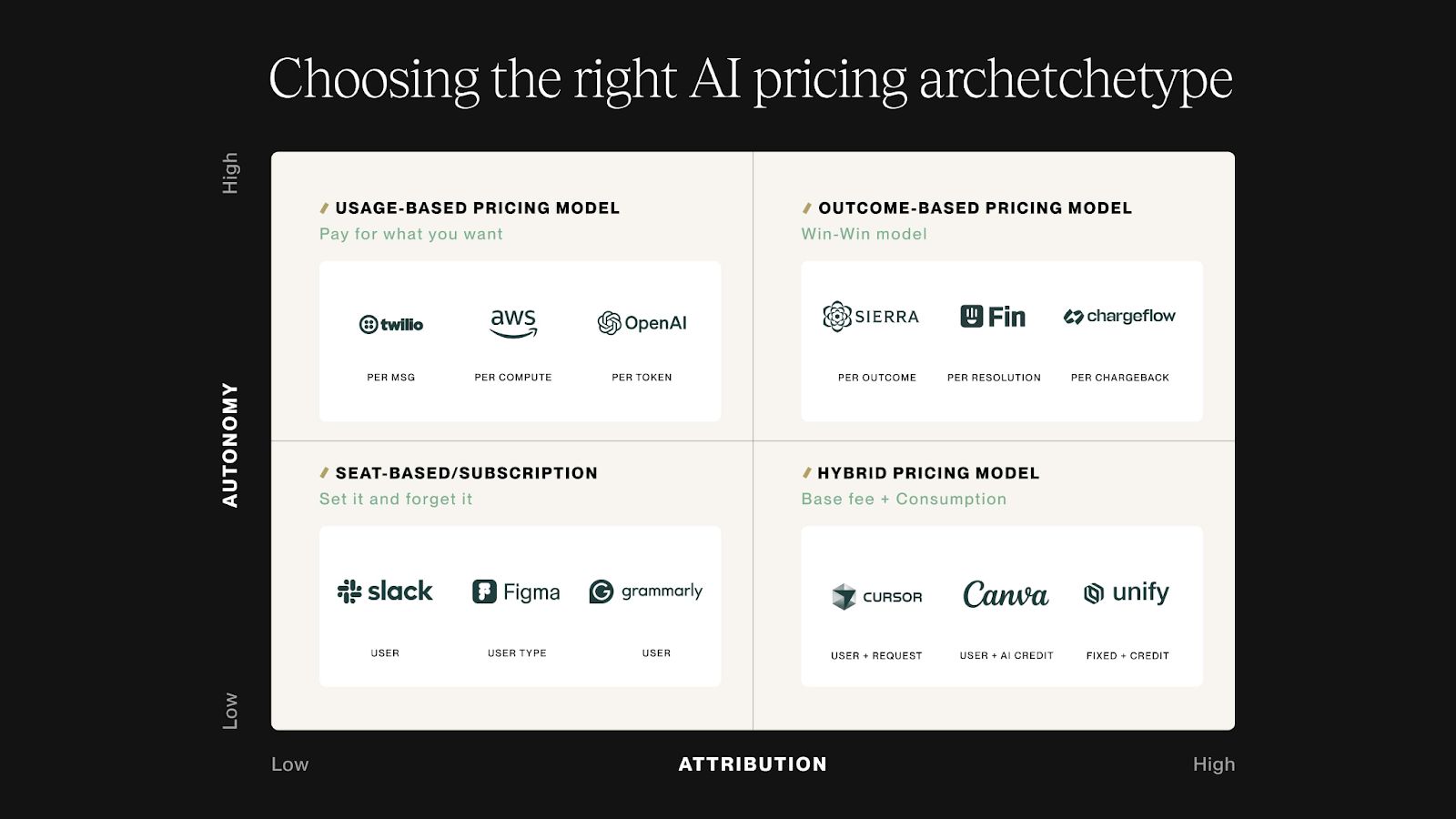

The fundamental issue facing AI-native software is a growing misalignment between the immense value it creates and the limited value it captures. The traditional seat-based subscription model hugely restricts the upside AI can generate, as it doesn't account for the dramatic efficiencies AI introduces, such as reducing the need for human labour.

While usage-based pricing offers a partial remedy, it still falls short. While AI-native companies increasingly embrace outcome-based monetization, there are still significant hurdles to the complex nature of the service work AI often performs; attributing a successful sale or an upsell directly to AI can be incredibly challenging, as many interdependent factors beyond AI contribute to such results

As a result, this leads us to a crucial inflection point: companies can either

Convince customers to adopt AI products with a new pricing model

Vertically integrate themselves with their customers

Dawn of Full-Stack Companies (Offdeal Case Study)

Full-stack companies, by definition, are technologically native service providers that leverage proprietary software to reshape their own operations and unit economics.

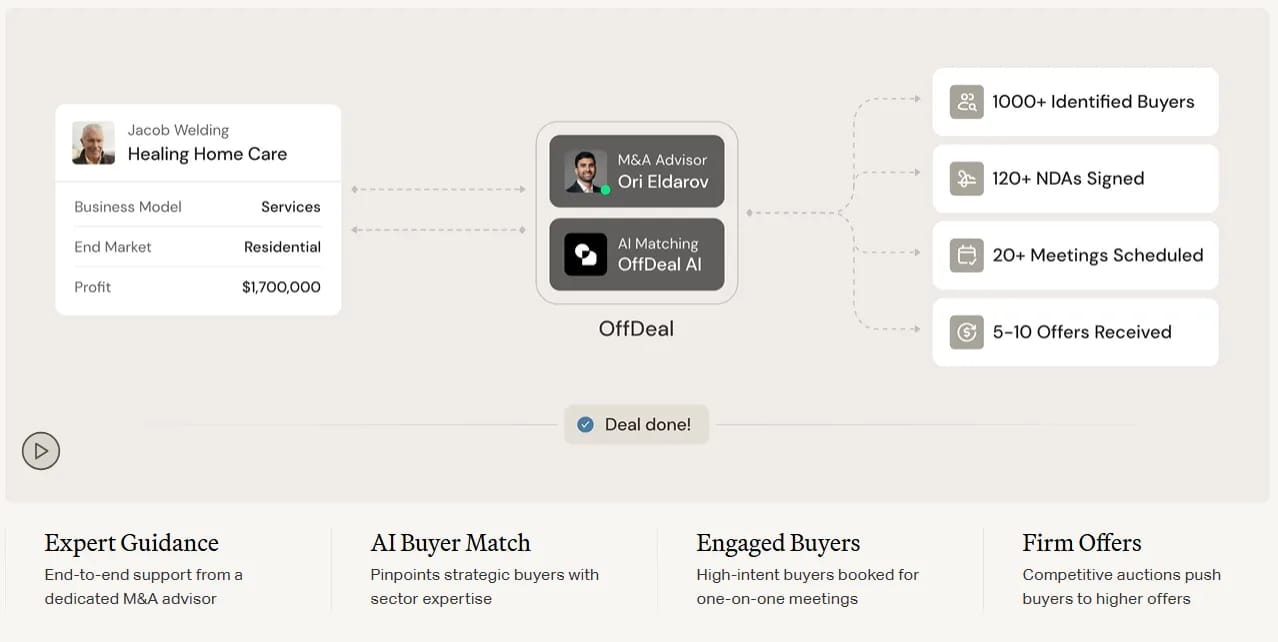

For example, OffDeal is an AI-native investment bank, founded by Ori Elarov, a former Vice President at the RBC Investment Banking Group. In an essay published by the founder, he stated that operating margins for investment bankers are incredibly low, with 60–70% of revenue consumed by compensation due to structural inefficiencies:

Handoffs between a layer of command (4-5 layers from MDs to analysts)

Missing context from untranscribed calls and historical documents

Manual re-work between deal teams

Culture of proof-of-work incentives (i.e., page count as a proxy for quality)

OffDeal's approach is a blueprint for the full-stack model:

Structural Organizational Redesign. Replace the five-layer hierarchy with the smallest team that can originate and close a deal. Junior time goes to judgment and outreach, not formatting.

Unified System of Record. Calls, e-mails, financials, buyer notes—everything feeds one datastore that AI agents or humans can query in a single call

Zero-Marginal-Cost Analysis. If an agent can screen and rank 10,000 buyers in less than ten minutes, “uneconomic” tasks become standard, compounding insight on every client touch

Couple this with AI technology to automate and accelerate tedious tasks, such as creating PowerPoint deliverables, conducting comparable analysis, identifying buyer fit, and answering diligence questions with verifiable knowledge.

As a result, OffDeal can operate at significantly higher margins, making it profitable to serve underserved markets like SMBs, where deal sizes are unprofitable for incumbents. In its latest fundraising announcement, Ori stated that Offdeal is now on track to achieve $10M in sales with over 30 sell-side mandates with only 2 full-time investment bankers.

M&A will always matter, but legacy banks are structurally unable to run AI-native workflows and therefore, will be unable to capture the full upside……. AI-first, vertically-integrated challengers will appear in each field. The post-AI world produces a clean slate for how human work will be done

Buy or Build? The Growth Buyout Opportunity

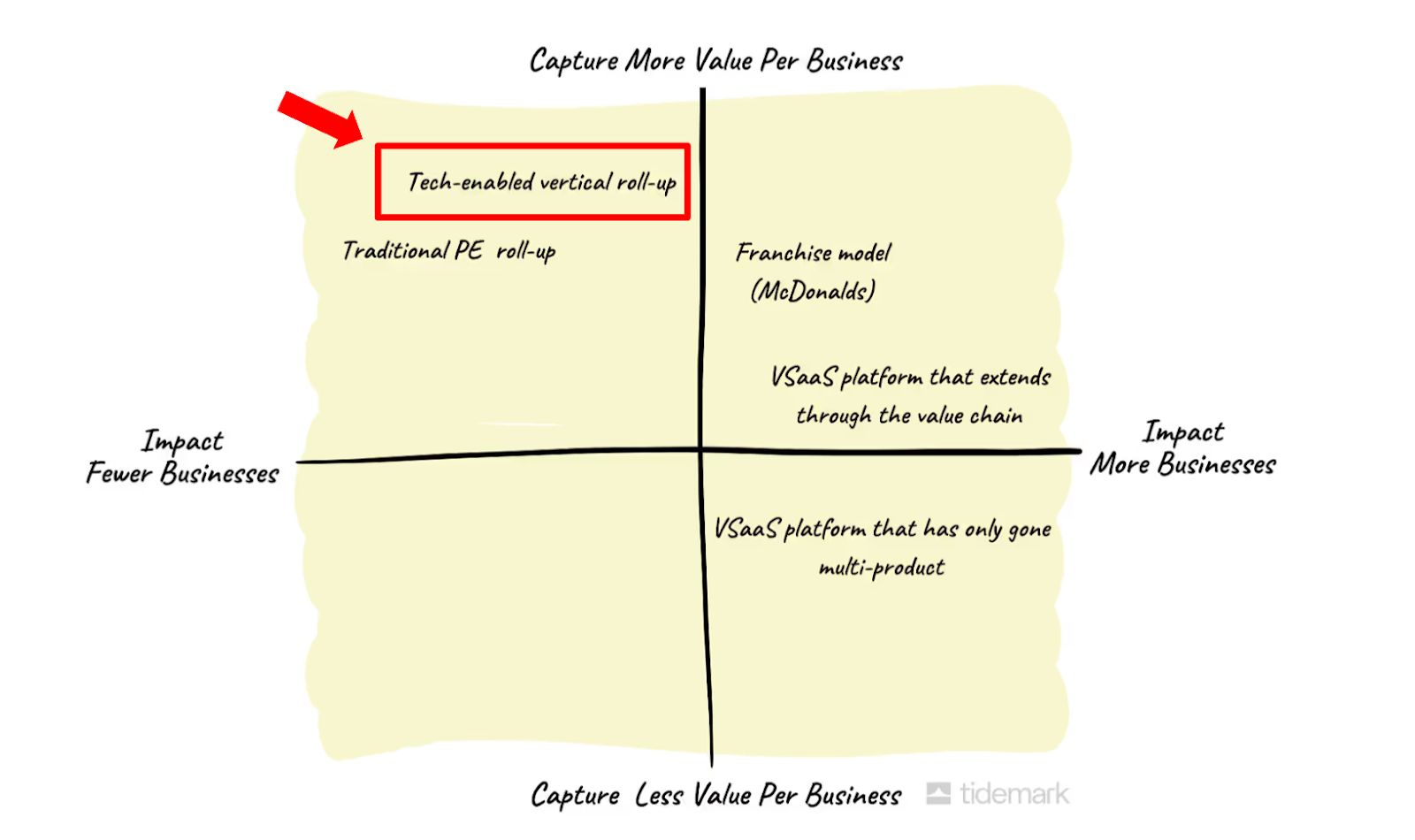

To take a step further, this "full-stack" imperative is precisely what defines the Growth Buyout (GBO) opportunity. GBO is an inorganic strategy for full-stack companies to scale not just through organic customer acquisition, but by acquiring and transforming their customers (i.e., service businesses).

Consider these examples:

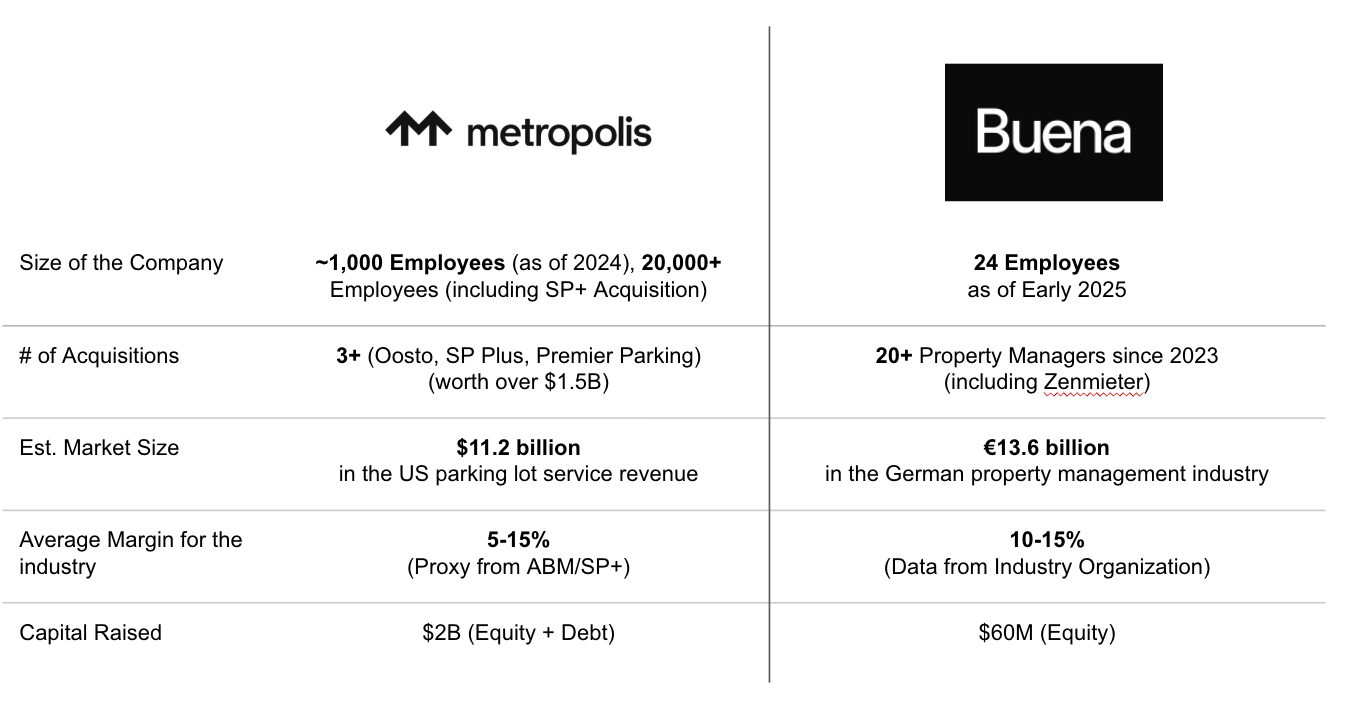

Metropolis: A parking technology platform that enables frictionless "drive-in, drive-out" experiences. In October 2023, Metropolis announced its acquisition of SP+, one of the largest parking management service companies, for $1.5B. This wasn't merely a software vendor acquiring a customer. It was a strategic move to access SP+'s 3,400 locations and 50 million customers, resolving a significant GTM bottleneck where facilities were locked into long-term contracts with incumbents. Metropolis acquired not just revenue, but the physical footprint and operational contracts necessary for direct transformation and control over the end-to-end service delivery.

Buena: A proptech platform for property managers. In July 2025, Buena raised $58M from Google Ventures and 20VC to fuel its acquisitions of property management service providers. Since 2023, it has acquired 20 property managers in Germany, a market notorious for talent shortages, low NPS scores, and 96.3% reliance on pre-cloud software..

Source: TechCrunch, Press Releases, SEC Filings

What Makes a Market Ripe for Growth Buyouts?

Growth Buyout is a high-risk strategy for software companies due to:

High Capital-Intensity: Requires significant upfront investment for acquisitions.

High Transformation Risk: Integration failures can wipe out synergies

So, what are the characteristics that would make a vertical viable for GBO?

Market Homogeneity → Do your customers share similar needs?

The market needs consistent customer needs and operating models. This allows for a repeatable transformation playbook. If every acquired business requires a unique approach, the model doesn't scale, and expected synergies are lost.

Verifiable Value Proposition → Is your solution proven to improve bottom-line?

The software's economic benefits must be measurable across customers. If the value proposition is fuzzy (e.g., "improves employee productivity without a bottom-line impact"), underwriting the deal and demonstrating ROI becomes impossible.

Margin Expansion Opportunity → How much margin can your solution lift?

The target industry must have significant structural inefficiencies, typically characterized by high variable costs (e.g., heavy utilization of labour) and ineffective processes (no software/legacy software practices). This is where the AI-driven substitution and synergization create real alpha.

Distribution Stickiness → How hard is it to get these customers on your own?

In sticky markets, roll-ups let you bypass the brutal go-to-market grind. The same inertia that makes it hard to acquire customers in the first place also makes them incredibly difficult to lose, ensuring long-term retention.

Long-Tail Customer Concentration → How fragmented is the service market?

The market concentration has to be sufficiently broad to allow for a range of acquisition targets beyond only "whales," enabling a programmatic roll-up strategy.

The Growth Buyout Trifecta

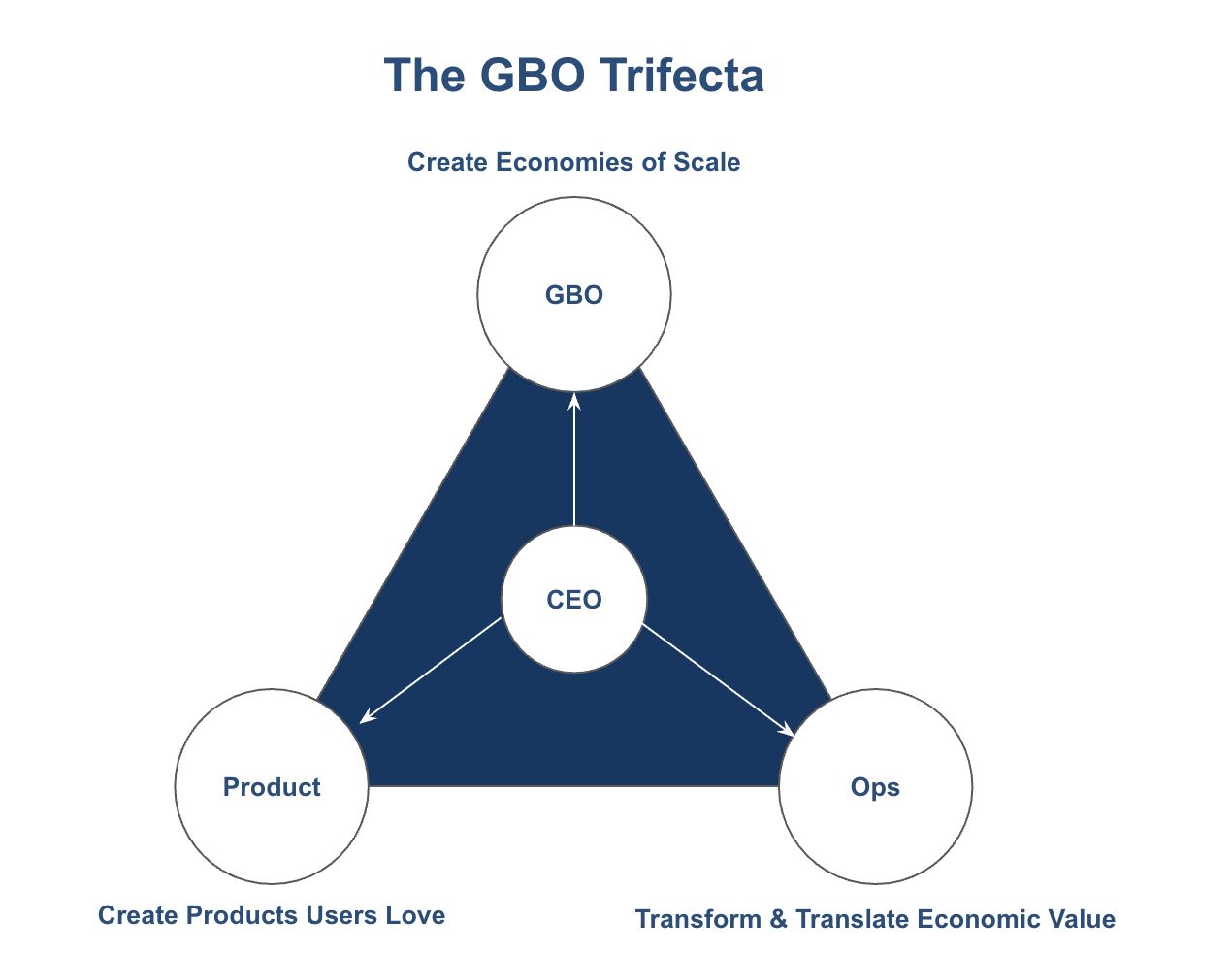

In the case of GBO, at the simplest level, the company will require three types of capabilities:

Product: This team builds the core technology that generates the margin expansion. In a GBO context, the "customer" is internal; it's the service delivery teams of the acquired companies. The product must be built for adoption and efficiency. It must be so good that it fundamentally changes how the service is delivered.

Corporate Development (GBO): This is the M&A function. It goes beyond traditional finance-heavy deal-making. This team is responsible for building and executing a programmatic M&A strategy. They are not hunting for one-off transformative deals; they are building a machine that can consistently source, evaluate, and close smaller acquisitions.

Transformation & Operations: This is arguably the most critical and most overlooked function. This team is responsible for realizing the value. They are the change agents who transform the acquired company and manage the end-to-end integration. This includes deploying the software, redesigning workflows, retraining staff, managing culture clash, and ensuring service quality is maintained or improved.

This emerging trifecta of needs will naturally complicate the business. Each capability requires leaders with distinct skill sets, often with conflicting incentives and goals.

GBO leaders must make coherent and effective capital allocation decisions across these three groups and invest in building the talent pool for each, particularly on the transformation and operations side, an constantly overlooked area they may not have been exposed to previously.

Rounding Thoughts

We’re in the early innings of the AI Services Wave, and its implications and possibilities are nowhere near finished emerging. The future of (vertical) SaaS is going to extend beyond software platforms.

We’ll see the rise of industry disruptors growing at an unprecedented pace, and incumbents in their respective sectors are rapidly investing in building and buying technology & AI capabilities to keep up.

And execution will be the ultimate alpha.

Resources